Last Updated on December 6, 2024 by underanewsun

Union Church of Pocantico Hills

It’s uncertain whether solace and redemption await you at the Union Church of Pocantico Hills in New York’s Hudson Valley. If, however, stained glass is what ye seek, ye shall find it there.

This little church, on a little hill, in a little town, on a long, winding down-home road is home to nine stained glass windows by Marc Chagall and one by Henri Matisse.

No neon signs announce the colorful treasures inside. Other than an occasional lawn mower and, of course, the obligatory dog barking in the distance, the church’s surrounding neighborhood is as mute as the ancient fieldstones on its facade.

The church is just 40 miles (25 km) north of Midtown Manhattan, but light years from the art galleries, museums, urban public spaces, and opulent private collections that usually host Marc Chagall and Henri Matisse’s ouevres. Seeing their work in such a reduced, intimate setting is rare.

The Rockefeller family was directly responsible for the small church coming to be. In the 1920s, the family donated land from their expansive Hudson Valley fiefdom, known as Kykuit, and assisted in its construction.

Curiously, the stone walkway leading from the parking lot to the church is composed of fieldstones in myriad shapes, sizes, and forms resembling the various geometric pieces of glass that compose the church’s stained glass windows.

Inside you’ll find unadorned white walls and tidy rows of straight-back wooden pews facing an austere altar. Rockefeller-style religion was sober and businesslike: sit straight, listen, pray, sing, leave, collect spiritual dividends in the hereafter.

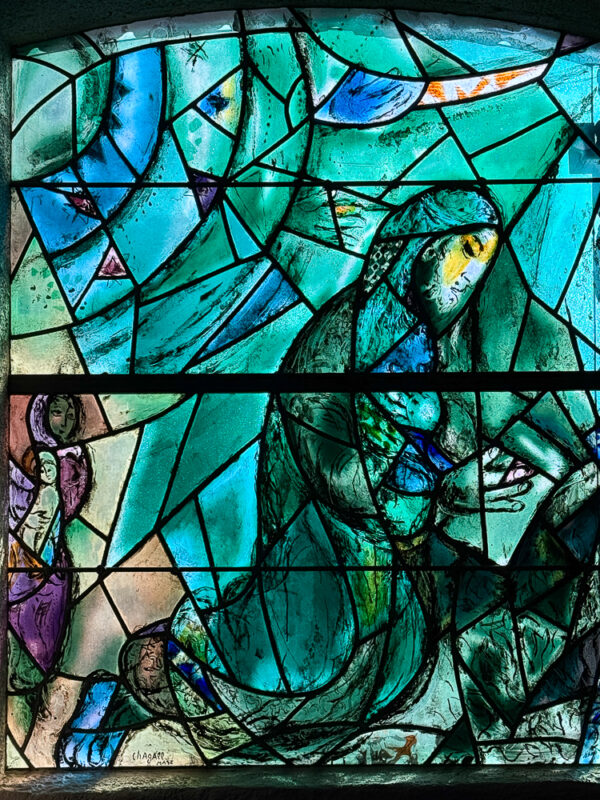

Matisse: King Chroma

In his early Paris years, Matisse was vilified as one of the ringleaders of Les Fauves (the wild beasts), a group of painters whose jaunty colors and rude brushstrokes upset the sensibilities of well-coiffed Parisian ladies and their starch-collared companions. They launched the art world equivalent of a pitchfork attack on Matisse and his chromatic cronies.

Years later, these same people declared Matisse the King of Color. The same ones who had labeled him a wild beast for his generous palette now kissed him on both cheeks, their smiles wider than the Champs Élysées. Can’t you just hear them? Why, sure, Henri and I go way back, bien sûr, baby.

Things were very different by the early 1950s. Matisse was in his 80s, sick, frail, and confined to a wheelchair. He would spend hours cutting colored paper into geometric shapes.

Matisse, the once reserved, bespectacled, studious law clerk-turned-seminal-painter now preferred his scissors to his brushes. He was done with formally working. Or so he thought.

Image © underanewsun.com, All Rights Reserved

The Rockefellers had known Matisse a long time. The doyenne of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, had been among the first to champion his vivid canvases in the U.S.

When she died unexpectedly in 1948, her family wanted to memorialize her with a stained glass window at the Union Church. And who better than her old friend, Matisse?

At the time, Matisse lived just a baguette’s throw away from Vence, a seaside village just minutes from the wondrous land and seascapes along France’s Côte d’Azur.

An order of nuns based there had convinced Matisse to design their new chapel. And, boy, did he design. The nuns aroused Matisse’s still firm creative muscles, prompting a four-year creative eruption by Mount Matisse.

During this four-year span, from 1947 to 1951, he designed the chapel’s architecture, altar, cult objects, pews, ceramics, holy water basins, chalice coverings, painted two stained glass windows and three murals, and chose the interior stone. Phew!

Heck, he even designed the priests’ garments. Had his trusty scissors been nearby, is it a stretch to think he may have ended up sculpting the priests’ hairstyles as well?

Too ill to attend the chapel’s opening ceremony, a priest read a message penned by Matisse.

It said, in part:

“…this work required of me four years of an exclusive and entiring effort and it is the fruit of my whole working life. In spite of all its imperfections, I consider it my masterpiece.”

Matisse Goes Up The River

The Rockefellers eventually convinced Matisse to accept their offer of creating a commemorative Rose Window.

And there she stands today, elegant, regal, its vibrant yellow, green, and blue tones greet visitors from the back of the church as if saying, Greetings, and thank you for coming!

Is it an abstract? Does the blue mean sky? Does green symbolize nature and yellow God?

Who knows? We do know the window’s maquette (scale model) was hanging on Matisse’s wall when he passed away in 1954.

Was he staring at it as the other side whispered its icy invitation? Were silent and ancient questions posed to the unknown: Does beauty need meaning? Or reasons to exist?

Perhaps he departed smiling, lungs empty, but soul filled with wisdom revealed at the last instant: less is more.

You’re Listening To Stained Glass Radio, With Your Host, Marc Chagall

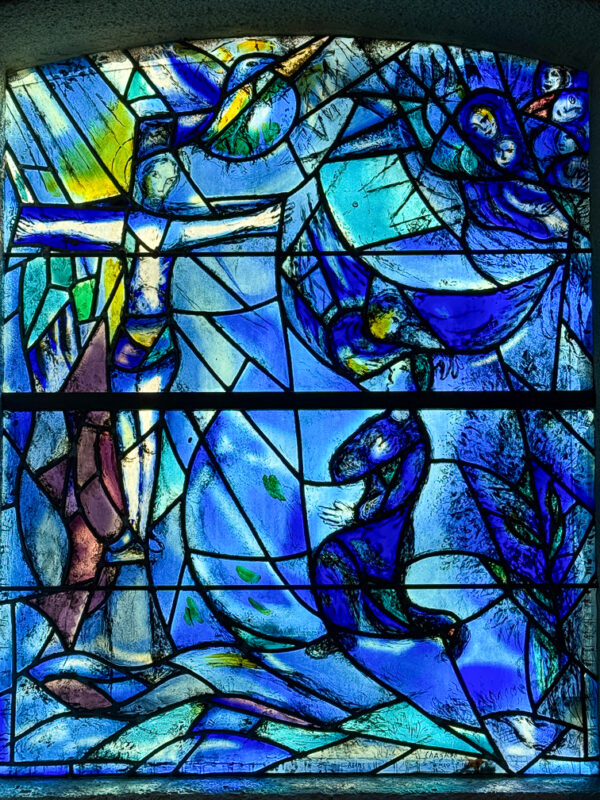

“I am out to induce a psychic shock into my painting, one that is always motivated by pictorial reasoning: this is to say, a fourth dimension.” Marc Chagall

Most people consider Marc Chagall a painter, when, in fact, he was a human transistor. Upon making contact with a canvas, his brush completed a circuit which began in his soul, traveled through a mysterious, cobalt otherworld (the fourth dimension?), zigged across his mind and zagged into our reality plane.

The unusual frequency Chagall tuned-in is timeless and otherworldly: floating farmers, loving brides, flying fish, fiddle-playing goats, scenes of shtetl life long ago. These vignettes cover the mind like a midnight snowfall in January–quietly…steadily…gently.

If Matisse’s Rose Window is the church’s Lady of Honor, then Chagall’s nine windows are its headline performers.

Eight smaller windows, four on each side, stand under the behemoth Good Samaritan window, which stands opposite, physically and aesthetically, to Matisse’s Rose window.

The Good Samaritan is the Generalissimo of the church’s windows. Upon entering, visitors’ necks snap upward in admiration.

Saturated reds, yellows, and greens are the counterpoints to the dense, dream-state, fourth dimension blue Chagall loved. It illustrates the biblical story of a man who helped another when others refused.

Chagall and his wife Bella had bolted from Nazi-infested Paris, landing in Vichy Marseilles. They were out of the fire, but still in the frying pan.

With the help of the Emergency Rescue Committee, a relief organization funded in part by the Rockefellers, the Chagalls were whisked through Spain and onto Portugal, where they secured passage to Gotham, arriving in New York in 1941.

Poor Chagall’s hand and back were probably sore from the many handshakes and back slaps that followed the Good Samaritan’s 1964 installation.

Perhaps in between the many bubbly-fueled compliments, he may have hinted he wasn’t averse to painting another two, three, or, say, eight more stained glass windows for the church.

Over the next several years, Chagall did just that. After his second window, the Crucifixion, he interpreted the stories of six Old Testament All-Star prophets: Joel, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Isaiah, and Elijah. A Cherubim-themed window completed this stained glass Praetorian Guard.

Along the way, some congregation members grumbled their church was transfiguring into a museum. In a way, it did.

Getting to the Union Church of Pocantico Hills

Driving to the church

Address: 555 Bedford Ave. (Route 448), Pocantico Hills, New York 10591

- Address: 555 Bedford Ave. (Route 448), Pocantico Hills, NY 10591

- Pocantico Hills is in Tarrytown, New York (same zip code)

- Enter Tarrtyown as city if GPS doesn’t recognize Pocantico Hills

- Church is closed during winter

- Learn more about the church

Public transportation from New York City

- Go to Grand Central Terminal (GCT)

- The train system operating from GCT is called Metro-North

- There are three main lines: Hudson Line, Harlem Line, New Haven Line

- Take a Hudson Line train to Tarrytown

- Avoid extra fees, buy tickets before boarding

- Whenever possible, take an express train

- At Tarrytown station, take a taxi to the church or arrange ride share service

- Address: 555 Bedford Ave. (Route 448), Pocantico Hills, NY 10591

- Church is about 10 minutes from train station

- More info on the church